Ignited Imagination

04 Dec 2024

The hearth brings us warmth and peace during these trying times

By KRISTIN LANDFIELD

To my small Hearth His fire came—

And all my House aglow

Did fan and rock, with sudden light—

'Twas Sunrise—'twas the Sky—

Impanelled from no Summer brief—

With limit of Decay—

'Twas Noon—without the News of Night—

Nay, Nature, it was Day—

—Emily Dickinson

When a chilly, damp wind blows across the plateau, it is hard to imagine anything more comforting than a hot, crackling fire. In her poem, Emily Dickinson sheds warm light on the way in which a glowing hearth can transform deep winter nights into welcoming light. I imagine that in her years of writing, foreign from the blue light of a laptop, the glowing firelight yielded even more significance than we can now appreciate. For her, the “arrival” of fire to her hearth is a transformative event—the ordinary space assumes an almost spiritual radiance. She connects a simple fire to a universal sense of light and hope. The hearth is more than a domestic comfort; it is a sanctuary for the soul. Unsurprisingly, the words “hearth” and “heart” are separated by a single letter.

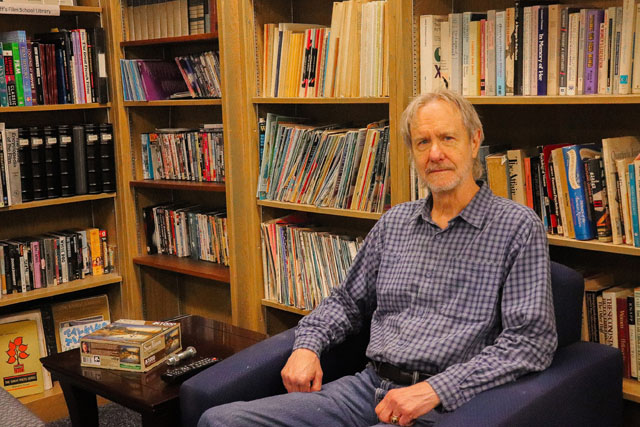

Recently, a friend shared some memories with me. He recounted childhood holidays spent with a part of his family that, as sometimes happens in families, drifted apart over time. By his teenage years, the family gatherings had waned to a single Thanksgiving event, during which sweet potato casserole and a warm popping fire shrouded signs of familial obligation. In these reflections, the fire is the centerpiece, where his uncle spent the day tending and nudging logs in the ample fireplace. Throughout the gathering, everyone would come and go, enjoying the flickering fire that kindly served my young friend a place at the hearth. As his uncle poked the logs and aerated the flames, he articulated a symbol of welcome that was not obvious the rest of the year.

This recollection emerged as we were talking about the appeal of a huge fireplace—how when properly built there is adequate draw to pull the smoke through the flume and to fill a space with warmth. What we were really talking about, though, was memory and belonging and a sense of ease in a confusing world. These holiday fires, lit and tended 40 years ago, still ignite my friend’s understanding of his own family legacy.

With the recent devastation and continued aftermath in the Southern Appalachians from Hurricane Helene, I am reminded of the sense in which we all need comfort and shelter. From our earliest ancestors, fire offered humans an unparalleled ability to create safe refuge and prepare a warm meal. We are all seeking serenity. It is no surprise then that, like my friend, we seem to have an almost innate sense of security tied to the idea of a fire and hearth.

There must be some limbic longing for a fire, not just for warmth alone (the way all organisms approach pleasure and avoid privation), but for the subconscious, a healthy fire affords a sense of ease. It offers cessation of uncertainty and sends a calming current through our nervous systems. A well-tended fire communicates that, for a time, all is right in the world. Few things ignite the human imagination as well as a mesmerizing fire. Even a screensaver image of a fire can have a soothing effect.

In Greek mythology, Prometheus stole fire from the gods and brought it to man. In many other traditions, a clever animal first obtained fire before sharing it with humans. According to Cherokee legend, the water spider spun a web to catch and carry fire from Thunder. Regardless of culture and myth, the powerful symbol of fire has fully integrated into our collective consciousness.

Early humans wrested fire from the landscape, learning to take advantage of natural fires and carry it to their dwellings. Depending upon how one defines “control of fire,” there exists paleontological evidence that Homo erectus manipulated wildfire more than a million years ago. Carbon records locate the earliest known hearths dating back over 250,000 years. Indeed, Darwin himself regarded the ability to manipulate fire as a peak human achievement, rivaled only by language in importance to humanity. According to Harvard biologist Richard Wrangham, the “cooking hypothesis” proposes that their ability to cook food allowed early hominids’ brain size to increase over time. It maintains that fire furnished the enhanced caloric intake required to fuel our large and demanding brains.

Fire proffered power to those who could utilize it. The use of fire afforded the lengthening of daytime activities and, therefore, the expansion of culture and gathering. Social complexity is the defining feature of Homo sapiens, reflected in our language and technology. Fire permitted increased social interaction, it provided safety during sleeping hours, and it developed culture through cooking and gathering. These benefits likely influenced key aspects of our species (e.g., bipedalism, social constructs, pair bonding, etc.). No human society, even in environments with mild temperatures and ample natural food sources, has ever been found without the use of fire.

It is not surprising then that, all this time later in our history, despite central heating and Gore-Tex boots, the fireplace still draws us in, even as a concept. A fire says that for these hours, we have enough. We may be scared, we may be hungry, we may be lonely, but we cozy up to a fire and even the darkest moments harbor peace. This winter, with so many in our region still reeling from the aftermath of September’s floods, may the glowing light of a warm fire offer profound comfort.