Finding Joy

02 Aug 2025

David Joy discusses writing, sobriety, and the necessity of speaking up in difficult times

August-September 2025

Written By: By Marianne Leek | Images: Photos by Kathryn Smith

David Joy once told my students, “Life’s too short for shitty books.” My family and I have always bonded over a shared love of books, initially finding Joy’s writing at an independent bookstore while traveling in Colorado. His first novel, “Where All Light Tends to Go,” was a staff pick, and when we were reading the blurb on the back, we realized he lived less than an hour away from us in western North Carolina. Early in his career, he regularly made time to have conversations with my high school students about books, the outdoors, fishing, and things that matter. Widely regarded for his kindness and unpretentious demeanor, Joy is one of the finest Southern writers of his generation.

A decade later, he has written four more critically acclaimed novels, and his essays can be found in several notable publications, including The New York Times and Garden & Gun. If you haven’t read his beautiful essay “David Joy’s Sweet Sorrow of Saying Good-bye to a Good Dog” about the passing of his beloved companion Charles Thomas, affectionately called “Chaz,” Google it immediately—and cue the ugly cry.

Author and Civil Rights advocate James Baldwin once said about writing, “You write in order to change the world, knowing perfectly well that you probably can’t, but also knowing that literature is indispensable to the world…The world changes according to the way people see it, and if you alter even but a millimeter the way people look at reality, then you can change it.” Joy speaks and writes with integrity, continuing to be a steadfast advocate and voice for others, while encouraging others to have the uncomfortable conversations necessary to help do the same.

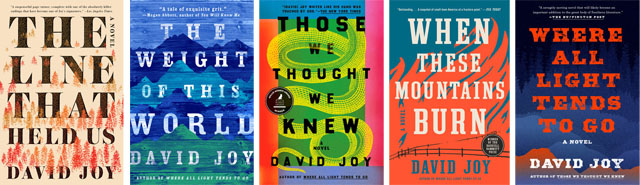

A master at lyrically creating a sense of place, Joy’s first three tautly paced novels are rooted in the kudzu-covered mountains of western North Carolina. Each has deeply flawed characters and explores themes of complicated family dynamics, poverty, depression, and addiction. However, his last two novels mark a shift in his writing: “When These Mountains Burn” addresses the growing opioid crisis in western North Carolina. “Those We Thought We Knew” examines systemic racism and the problem with Confederate monuments, while shedding light on the removal and relocation of an AME church and its cemetery to make way for a Western Carolina University dormitory.

While Joy acknowledges this shift from simply telling a darn good story to one with a more complex social message, he says it was not so much intentional but more an instinctive responsibility to bear witness to things he was noticing in his rural community. In the case of “When These Mountains Burn,” it was the opioid epidemic that had become an unignorable part of his daily life. “I was living just over the county line into Haywood at the time, and I’d go to the post office to check the mail, and the parking lot would be covered in syringes. I’d drive through town and see medics pulling bodies out from under bridges or out of gas station bathrooms where people had overdosed. Addicts were knocking on my front door and asking for sewing needles to skin pop.”

Showcasing some of Joy’s finest writing, “Those We Thought We Knew,” published in 2023, is part small-town murder mystery, part lyric poetry, which forces the reader to take a hard look at regional and oftentimes generational familial beliefs regarding racism, heritage, and hate. Joy explained that it took over a decade to write, with his other four novels written “while I was trying to wrap my head around this story. In a lot of ways, it feels like the book I was put on this planet to write. The heart of that novel is constructed of questions I wrestled with for most of my childhood and conversations that I wish had been had.”

“Those We Thought We Knew” is not only a work of Southern crime fiction with a powerful social message, at its heart, it’s also a profound love story about a deeply connected grandmother and granddaughter, the poetic final chapter circling back to the two dancing and singing in their summer garden to the music of western North Carolina native, Nina Simone. It may be one of the most beautifully written endings in modern American literature, one that transcends genre.

With the protagonist Toya’s grandmother being deeply immersed in her rural community and church, as well as Toya’s installation art centering on the removal of the AME church, the church feels much like a secondary character. Joy explained: “There are a lot of subtle things happening in this novel, particularly regarding the role of the Black church. The book starts with the true story of a church that was founded by eleven formerly enslaved individuals being removed to make way for a dormitory on Western Carolina University’s campus. I think one aspect that I was really interested in was the idea of these churches as community centers, particularly in rural places. There’s a moment in that novel when Toya is talking about that removal, and she says, ‘That building had to have been the center of their universe. That church must’ve felt like gravity.’ I think that’s true. I think that oftentimes these churches became the hubs that hold everything together.”

“There’s also this idea of the Black church as a place of resistance. You think about the way that these buildings were used as spaces to organize during the Civil Rights movement. You think about the words King wrote in ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail.’ John Lewis talked about this, about this connection between the church and Civil Rights, when he said, ‘Slavery was our Egypt, segregation was our Egypt, discrimination was our Egypt, and so during the height of the civil rights movement it was not unusual for people to be singing, 'Go down Moses way on down in Egypt land and tell Pharaoh to let my people go.’ The church plays a really interesting role in that regard, and so there was just no way to tell this story without incorporating some of that reality.”

To use two Joy-isms, “Those We Thought We Knew” has recently “grown legs,” encouraging more people to “swing the ax,” speak out against racism, and advocate for others. However, while a lot of people consider themselves to be anti-racist, they haven’t yet found the courage to use their voice in such a public way or start those difficult conversations. Doing so requires honest self-reflection, reckoning with family history, taking a hard look at generational beliefs and values, and making a conscious effort to both unlearn what has been taught and do better with this next generation.

Joy insists it’s not only necessary, but that meaningful change can happen within the ebb and flow of our daily lives. Transforming the collective culture of white America begins in our homes. “I remember having a reading once, and a White woman stood up and said, ‘But what if [speaking up] gets you killed?’ I was taken aback, and there were a lot of things running through my mind at that moment, chief of which was that it strikes me as an immense privilege to have that choice, particularly when talking about the protection of those who don’t have a choice, who live in perpetual danger of very real violence. But what I told her was that the conversations do not have to be these big, public displays. You don’t have to go march in the streets if you don’t want to. The majority of these conversations need to be had at the dinner table, on car rides, on front porches, sitting next to people close to us.”

“White people in this country have a serious reluctance, and often outright refusal, to be made uncomfortable. Quite simply, we are not having these conversations, and even when forced, it is not for any meaningful period of time. That is a matter of privilege. We don’t have those conversations because we do not have to have them. Nothing noticeable changes for us by not engaging. Our lives remain the same. I hear these ideas of ‘shame’ or ‘White guilt' tossed around often as this sort of ridiculous side-stepping. It’s a convenient way to avoid being made uncomfortable or having to engage in conversations about injustice. I am the direct descendant of enslavers. My family lines on both sides are filled with men who fought to preserve that institution. But I do not feel shameful about that. I do not feel guilty. What I would feel shameful about and guilty for would be recognizing that 160 years later I still sit as a direct beneficiary of that institution, and keeping my mouth shut. That would be shameful.”

Joy has done the heavy lifting to start the conversation. This past spring, a video of him speaking “on the fly and from the heart” at a Jackson County Commissioners meeting went viral on social media. “I didn’t realize that any of that was being recorded, so when it started appearing on social media, I was really surprised. It wound up reaching millions of people, and that’s pretty shocking to think that something I said in that room at the Justice Center in Sylva echoed that loudly.” In the video, he addressed commissioners and criticized the removal of two plaques from a Confederate monument that had initially been installed in 2021 to cover up the Confederate flag and an inscription that read, “Our Heroes of the Confederacy.” His words resonated with viewers and those who follow him on social media.

“There was a woman who stood up after me who said some things that I felt were really important, and I wish that those comments had gotten the same attention. She pointed out that there were 218 people enslaved at the time of the last census, leading into the Civil War. So, setting aside the Jim Crow context of how that statue wound up in front of the Jackson County courthouse, those commissioners are fighting tooth and nail for a statue that memorializes 164 soldiers from Jackson County while telling every descendant of those 218 that they revere the time their ancestors were in bondage. She also read the names of every enslaver in Jackson County, a list that included the surnames of every county commissioner but one. I thought that was incredibly powerful. All of that to say, there are lots of people swinging the ax, and for the most part, it is an act that goes unnoticed.”

Joy grew up in Moore’s Chapel, a rural community that has since been swallowed up by the inevitable expansion of Charlotte. He moved to Cullowhee to attend Western Carolina University, and following graduation, he put down roots in Jackson County. Much has been made of the fact that Joy was not only a student in Ron Rash’s fiction writing course, but that the two have become great friends, bonding over both a shared love of language and fishing.

Joy credits Ron with introducing him to the “right books at the right time,” inevitably steering the early trajectory of his writing career. “I was never a big reader as a kid, and looking back, it was because I just never got my hands on the right things. I’ll never forget him giving me a copy of William Gay’s “I Hate to See That Evening Sun Go Down.” That was the first time I’d ever heard my people and seen places I knew on the page.

Until then, I didn’t realize you could tell those types of stories. That was a pivotal moment for me as a writer. That book led me to all of William’s other works. William led me to Larry Brown, Larry Brown to Harry Crews, Crews to Daniel Woodrell. I think those were the big four for me early on. They sort of make up the ground where I’m rooted. The influences have really shifted and expanded since then to everyone from Jeanette Winterson to Randall Kenan, but those four will always sort of be the pillars for me. That’s where I cut my teeth.”

I once heard Joy say that he doesn’t trust writers who aren’t readers. I asked him about the writers and books he’s currently excited about. “That’s a big question and a long list. I tend to avoid fiction when I’m head down in a project, so I haven’t been reading many novels of late. I’ve read a lot of great nonfiction, though. “Enough” by Melissa Arnot Reid and “Cipher” by Jeremy Jones both stand out. I also read a beautiful new collection of poems recently by Noah Davis called “The Last Beast We Revel In.” But as far as writers who genuinely excite me, two that immediately come to mind are Maurice Ruffin and Crystal Wilkinson. I know Crystal’s working on a book of nonfiction. Maurice is working on a new novel. Both of those are easy preorders for me.”

Readers can look forward to an upcoming novel called “Del Rio,” which Joy says is a return stylistically to his early writing. “It’s dark and gritty and fast, more character study than social critique. I think these last two novels were trying to do some really big things, and I think I felt really disappointed in the reception. In a lot of ways, I allowed that to take some of the fun and passion I have for writing. When you try to take risks and do these bigger things, and you watch it go unnoticed, it takes a toll. This novel is an attempt to reclaim that joy for myself. I wanted to just write a fun book. I wanted to write a love story. I wanted to turn the idea of the happy ending on its head. It’s a book that’s really playful with form and voice, and I think that’s just been a lot of fun for me.”

Joy also shared that he’s been working on a television show that is a spinoff of PBS’s award-winning “Southern Storytellers.” He explained that it features him and Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Jericho Brown interviewing writers, artists, and musicians outside of the South. At the time of our interview, Joy said they recently interviewed five-time Grammy winner Samara Joy in New York City and novelist S.A. Cosby. The show is expected to be an eight-episode offshoot of the second season of “Southern Storytellers.”

In addition to his participation in “Southern Storytellers,” 2023 marked the release of the film adaptation of “Where All Light Tends to Go,” which was re-titled “Devil’s Peak.” Despite that, it included Billy Bob Thornton and Robin Wright, as well as Wright’s son Hopper Penn. “Devil’s Peak” saw a limited release and virtually went straight to streaming. Historically, Hollywood seems to have a difficult time getting Appalachia right. I asked Joy his thoughts about this. “I don't think 'getting Appalachia right' is ever the goal or even in the conversation. I think the greatest difficulty with adaptation is Hollywood spin. It's abandoning the original story for a belief that something else will sell. I think if you're going to adapt something, you have to trust in what exists on the page and you have to cling tight to that, otherwise you have no business trying to tell that story. A story where Jacob McNeely survives is not "Where All Light Tends to Go.” Daniel Woodrell's “Winter’s Bone” is an example of when an adaptation works well, and it was because they stuck to the story. It's actually really simple.

Over the past decade, Joy’s readership has grown exponentially, with thousands of new readers recently finding Joy, due in part to the viral sharing of the recording of him speaking at the Jackson County commissioner’s meeting. He is grateful for new readers and those who have been with him since the publication of his first novel and hopes longtime readers recognize and appreciate the evolution of his craft.

“When I think about the writers, artists, and musicians that I appreciate most, growth, evolution, expansion, those are the things I value in their work. I don’t want to read the same book twice. I don’t want to hear the same album. I don’t want to stare at the same painting with the same colors and textures and subject. I want to watch the body of work open like a firework. I want the lens to widen, even if it's a tightening down of the lens, a tightening down of focus; I want the show to get bigger. I want there to be a noticeable honing of craft. I want the levers to be less visible, for things to feel more fluid. The magic trick should never feel like an illusion. It should never feel like a trick. So all of the things that I want from the artists I admire, that’s what I hope the people who are following me feel like they’re getting from my work. I hope that’s what they feel like they’re witnessing.”

I asked Joy to discuss his overall body of work, which novel he’s most proud of, and a work he wishes he’d authored. “It’s hard for me to pinpoint a single work. There are things I love about all of them. “Where All Light Tends to Go” was the first novel I ever wrote, and there’s something magic about that. Those first three novels are sort of grouped to me stylistically, and I think “The Line That Held Us” was really me at my best within that early style. These last two novels have been social novels in ways that those first three weren’t, and I’m proud of the work those books are trying to do. "Those We Thought We Knew" just took so long and was such a hard story to get right. It was assuredly the most challenging story I’ve tried to tell. I’m proud of how it came out.”

“As far as one book I wish I’d written, maybe Daniel Woodrell’s “The Death of Sweet Mister.” That book is just so tight and has such a masterful understanding of voice, and it’s the type of story I love most—rural, raw, cavernously dark. I reread it a couple of months back, and the whole time I just kept thinking I wish I’d written it.”

Earlier this year on Instagram, Joy candidly discussed his battle with depression and his decision to get sober. Understandably, he received an outpouring of support and encouragement from people responding to and connecting over a shared struggle. “I think it started with just a recognition that there were a lot of really big decisions that needed to be made, and knowing that I did not wish to ever look back and wonder if those decisions had been made through a fog. That was initially why I got sober. Once those decisions were made, though, life got really unsettled with a lot of moving parts, and during all of that, I realized that the only two things completely within my control were exercise and sobriety, and so I clung to those two things. I wish I could say there’s been some transformational moment, but there hasn’t. I’m still trying to juggle a whole lot of things with hands that don’t seem built for juggling. But in times when so much is outside of our control, I think that it's particularly important in those moments to hold tight to the things that are, and so that’s what I’m doing.”

Joy seems happy and at peace. If you’ve followed his journey over the years, then you know he’s most at home outside—on the lake, by a stream, or in the woods. “I think the woods are one of the few places where my mind goes empty. I treat that space like church.” And perhaps it’s there, outside—whether in western North Carolina or the Pyrenees mountain range in France—where Joy finds joy.