A Grief Observed

04 Aug 2021

A Highlands therapist shares about the loss of her brother during COVID-19

By Kristin E. Landfield

Today we live in a strange shadow of the recent pandemic. For many, it feels like we’ve left COVID-19 in our wake. Perhaps most in our community have been vaccinated and feel free to interact without restraint. Perhaps we left our concerns by the wayside when the CDC lifted mask ordinances. Perhaps our cognitive capacity to sustain heightened concern for this invisible and changing virus is saturated, so we’re unable to maintain the same vigilance. Regardless, we have turned a corner and life is beginning to resemble a version of normal.

Here on the plateau we are fortunate to find fresh air in abundance; there is space to breathe and feel safe. It’s become easy to forget the veracity of this puzzling and devastating phenomenon. Despite the real suffering many in the region have felt during this pandemic—loss of all kinds—we who live in western North Carolina were somewhat buffered from the intensity felt in dense urban centers. Most of us weren’t under that same assault of fear and restriction as many people around the world. I wonder, however, if our locale has also buffered us from recognizing the profound grief and loss COVID-19 has created.

This last year and a half have been nothing if not disorienting. No event in modern history replicates the universal threat we’ve experienced since February 2020. Historically in times of distress, communities unite to weather life’s howling storms; they bring company to the housebound and hugs to the weary. Paradoxically, measures to quell this virus inherently constrain the customs that sustain us during life’s inevitable trials. One could argue that COVID-19 has been as much of a mental health pandemic as an immunological one. Those most vulnerable to struggles with mental and emotional wellness had fewer connections and resources to alleviate their troubles. Loneliness compromises immune defenses and inhibits the body’s ability to fight infection. It’s been a tragic cycle on many levels.

Right now, so much of what we see in the aftermath are supply-chain disruptions to the economy and delays with commodities we took for granted. So we grumble, but may forget the tragedy that gripped the last year still holds many of our neighbors. Their luxury of grumbling over lumber prices was seized, losing a loved one to COVID-19. They’re mourning while the world moves on, deciding we are tired of talking about it and thinking about it and accommodating it. And for those of us who can, it’s right to celebrate some return to normalcy, to appreciate the pleasures we once took for granted, to experience joy and gratitude for the people who bring richness to our days.

Unfortunately, many are still coping with the loss of a loved one during this time; pain pays no regard to political affiliation nor opinions about the shutdowns. Perhaps the saddest reality of this era is how many have been sick and suffering alone (with and without coronavirus) and

how the disease itself impeded our cultural rituals and customs around sickness and death. Humans are social, and in times of distress, it’s our loved ones and community that comfort us and help us through. We’re understandably tired of shaping our lives around the pandemic, but we can still honor the experience of our friends and neighbors who will need comfort in the weeks, months and years to come. That comfort may appear in the form of professional counseling.

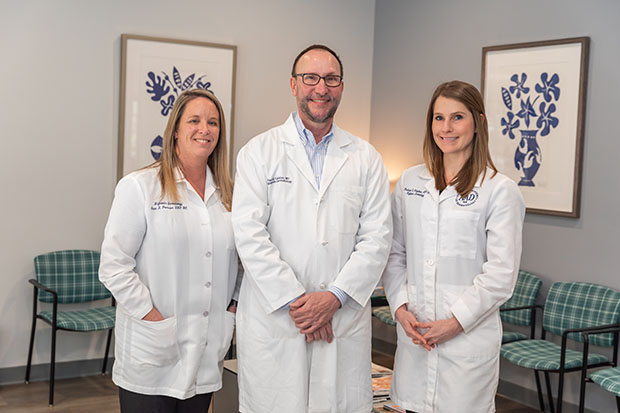

The Counseling and Psychotherapy Center of Highlands (CPCH) provides support for a broad spectrum of mental health needs; among them are resources for those experiencing the lasting effects of the pandemic. Many who avoided the virus still lost financial security, daily structure or are struggling with increased substance misuse. Many who lost a loved one haven’t had the customary support because of social distancing requirements; a professional counselor can help navigate the compound grief of loss and loneliness.

Below, Jeanne Thiele Reynolds, a licensed marriage and family therapist (LMFT) and ordained minister (PC/USA), shares a reflection about her experience losing her brother to COVID-19, an alternative look at guilt and the grief process.

For more information about the wide range of services available at CPCH, please contact Anne Koenig,LPC, RPT-S, (annekoenigpc@gmail.com), Jeanne Thiele Reynolds, D.Min, LMFT, (jeanne.thiele.reynolds@highhopecounseling.com), or Tracy Stribling Franklin, LCMHC (tracy.stribling@gmail.com).

Reflection On My Brother’s Death:

Rethinking Guilt & Grief, May 2021

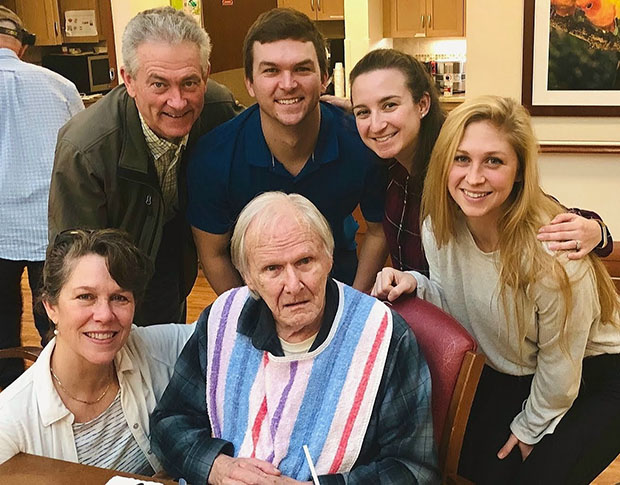

My brother Richard died on December 15, 2020, during the third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. I was told that he died from double pneumonia, but I suspect that the Department of Veterans Affairs long-term facility where he resided gave this diagnosis rather than report the more harrowing one. Regardless, he died after nearly a year in COVID lockdown without family visitors. Yes, we occasionally spoke by phone, but my calls to his understaffed unit frequently went unanswered. Even when we could connect, Rick’s hearing, speech and unpredictable clarity of mind made meaningful communication challenging.

The last time I saw Rick was in March of 2020. My husband and I drove the nine hours to Orlando like we’d done several times a year for decades. It was good to see him in person, and he seemed glad to see us too. I remember so many details that take me right back to the facility’s sunroom that day, the laughter, Rick’s more coherent conversation, and the haunting question Rick asked while walking back to his private room, “Is this where I live now?” He had never asked this before, and when I sadly replied, “Yeah, you live here now,” he seemed to surrender to his reality.

The following day we’d planned to say goodbye before heading home but were informed his facility had initiated a “no visitors” policy over increasing concerns of COVID spread. Little did I know I’d seen my brother for the last time; the pandemic would surge and outlive him.

There is always grief that accompanies the final goodbye to a loved one. Grief escorts us on the road of re-membering, to the realization that the visits of so many years will be no more. Grief befriends us to give us space to mourn our loss, to recognize the power of love we hold so dearly - so tenderly in the depth of our souls. Grief gives us permission to experience the totality of what it means to be human—to love and be loved and to belong and connect more deeply with ourselves and others through our relationships. Grief is the ultimate and inevitable part of loss.

And then—stealthily, from the shadows of our re-membering creeps in the shroud of self-doubt: Guilt.

I fought off my feelings of guilt by rationalizing, “I wasn’t allowed to visit him;” by intellectualizing, “guilt is unproductive; a waste of energy; a feeling.” I was reminded of all the same words I have said to those with whom I work in grief counseling - and continue to support. However, coming to terms with this COVID guilt of not being present to say “goodbye” to my brother (a guilt that has continued to poke at the back of my grief process) has given me a new understanding of guilt.

The COVID pandemic quarantine denied us the natural inclinations to cleave to the ones we love - and the hope that our presence might have made a difference. Many who have lost loved ones during this pandemic may understand this guilt of which I am speaking: “She died alone.” “I was not there with him.” “I did not do enough.” So, it is understandable that we who “failed” to be present with our loved ones in their final hours would invite guilt to help us sort out how this loss might have turned out differently - of how we might have miraculously constructed a more Rockwell-like ending. And it is guilt that often awakens us in the middle of the night, grips us by the chest, forcing upon us a scene-by-scene replay that reminds us of how we might have made things right if we had just tried harder, done more, been more.

Perhaps guilt’s intention is to help us try to make right what we feel has gone terribly wrong. We want to believe we could have done SOMETHING, ANYTHING to have had a different ending. Could it be that we would rather entertain guilt than realize how impotent we are to affect outcomes? Guilt helps us hold onto the illusion that we are more powerful than we are. Perhaps it is easier to entertain guilt than realize how impotent we are to transform circumstances around death.

So, there it is. Guilt helps distract us from fully embracing the pain of untimely goodbyes. On a personal level, it buys time to process the reality that maybe we take life for granted –and helps us realize how precious it is. Guilt invokes in us the depth of love we can experience but rarely acknowledge. Guilt “re-members” us to our memories – to shared laughter and tears, to our longings and belongings, to our deepest desires and to our capacity to love and to be loved. And perhaps guilt ushers us toward forgiving ourselves for our powerlessness.

Collectively, this COVID pandemic has given us the unique experience of worldwide grief, national grief and community grief— amid all our family and our personal grief. It has given us permission to share our humanity, to experience the breadth and depth of our emotions, to reach outside ourselves and connect in a shared experience of love and loss that only this grief can provide. It is this love that promises true healing, forgiveness and wholeness - to rise up out of the depths of our judgments, perceived failures and losses - and of death.

Guilt, which is masterful in distracting us from slipping into lingering despair, is also instrumental in drawing attention to our individual and collective capacity to love. Guilt is a form of protest against realities beyond our comprehension and our inability to change them. Guilt is a testimony to our desire to hold onto those we love and to accept at our core that we cannot. Guilt, when looked at as a natural part of the grief process, is the part of the journey that leads us to our most vulnerable selves and our aversion to face our limitations, our brokenness and our deep longing for connection. Interwoven in the grief process, guilt may help us reconnect to what it means to be truly human- the acceptance of our limitations, the forgiveness for all we are unable to control, and the faith in the reality that we all are born from and die into everlasting love.

For those to whom we have been pressed to say “goodbye,” we know love more fully because of you. Be at rest in the arms of love.

Jeanne Thiele Reynolds, D.Min., LMFT

Thanks to Gillian Treadwell, MD and Carlye Reynolds, JD - for help with editing.