Fresh Mountain Air

03 Jun 2025

Highlands and the legacy of Mary Lapham

June-July 2025

Written By: Story and photos by KRISTIN LANDFIELD

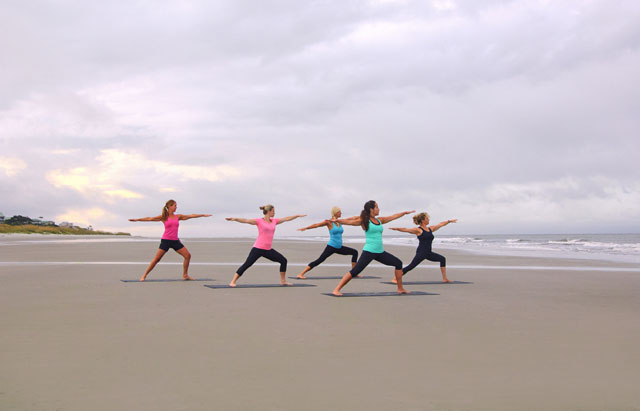

It is summer, and green is the theme in the mountains. Lush vegetation covers the rugged plateau. Along the ample hiking trails, ferns and perennials spill into the pathway. The forest teems with life, as the long days of summer’s protracted light fuel the engine that is our vibrant ecosystem. Along with that energy comes summer’s heat. Several weeks ago, after an evening walk on one of the first really hot days, I sat on my porch and enjoyed the coolness of the evening wind that jostled the fronds on my potted ferns. The wind brought a sense of renewal to the moment, and the words “fresh air” came to mind and lingered, as I thought of too much time spent indoors or driving or detached from my surroundings. Here, though, was a moment where the freshness from the evening air brought a sense of peaceful hope, almost as though summer was sighing. Music from the night bugs played atop the evening breeze.

Those who flock to the mountains in search of fresh air understand its healing aspects. We are rejuvenated and invigorated by a summer breeze, cool, dewy mornings, and a slight chill on an Appalachian evening. There was a time, however, when seeking fresh air was prescriptive—it was not only soothing; it was the solution.

In the early 1900s, tuberculosis was a leading cause of death in the United States—a slow, torturous decline during which the sufferer’s lungs slowly fill with fluid and asphyxiate. Tuberculosis patients sought treatment and care by visiting sanitaria, which were growing in popularity to heal the sick and keep the spread of lung disease at a minimum. Poor ventilation increases the spread of tuberculosis, an infection caused by bacteria, which is exacerbated by close quarters and stagnant conditions. When an infected person coughs, these bacteria are released into the air by tiny particles called droplet nuclei. Naturally, open air and space to heal inhibit the expansion of the debilitating condition.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, sanitaria appeared throughout western North Carolina, considered a haven for those suffering from tuberculosis. The climate, fresh mountain air, was the tonic for those with consumption. The area became a mecca for those studying climatotherapy. Highlands in particular became key healing grounds for those seeking relief with the healing power of clean air.

In the late 19th century, Mary Lapham and several friends visited Highlands. They decided to stay and become active in Highlands’ social life. Lapham eventually purchased a home on Satulah Mountain that she named “Faraway.”

But her lifelong interest in medicine, specifically in treating lung diseases, continued to grow. Mary left Highlands to pursue these studies. After graduating from the Medical College of Philadelphia, she traveled abroad to study innovative techniques in Munich. When she returned to Highlands in 1908, Dr. Mary Lapham, a pioneering physician focused on pulmonary conditions, founded Highlands Sanitorium.

Lapham established Highlands Camp Sanitorium on a 15-acre tract of what is now Highlands Historical Village on North 4th Street. It comprised a three-story house for its primary structure and sixty tent-cottages, known as the tent of Bug Hill. These tents were wooden structures with canvas flaps that opened to the crisp air. Lapham’s treatment methods were paired with the prescription of sleeping out-of-doors, allowing this magnificent plateau to support the restoration of patients’ lungs.

While practicing in Highlands, Mary Lapham pioneered an innovative technique in which nitrogen is injected into a tubercular lung, creating a forced compression that allows it to rest and heal. She was the first to successfully apply this pneumothorax technique in the United States and the first to publish her findings.

In 1918, a fire destroyed vital equipment, and Mary Lapham ended her medical practice in Highlands. However, tuberculosis patients continued to receive care from her nurse, who moved 25 of the tent cottages to her family property.

In 2018, the Highlands Historical Society gathered to honor her impressive legacy and its impact on medicine with a North Carolina Highway Historical Marker that reads: Mary Lapham 1860-1936 Physician; innovator in the treatment of tuberculosis. Served in Europe, WWI; operated a sanatorium here. 1908-1918.

This brief epitaph belies the significance of her work. Hundreds of patients were successfully treated as a direct consequence of Mary Lanham’s calling. However, the very air itself was the prime mover in her cause. Those who find solace in these beautiful mountains know that simply resting in their presence confers a tonic hard to replicate anywhere else.

Several years ago, I was hiking on Satulah, not too long after first learning of Mary Lapham’s legacy. It was the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, and I was keenly aware that open space is a precious gift. As I ascended the path, a billowy cloud of fog descended among rich ferns, drooping boughs of young hemlocks, and the “doll’s eyes” fruit of white baneberry. It funneled down the path, engulfing me almost as if in a dream. I remember it being a muggy day, and it seemed as though the morning breeze offered me a cloud for refreshment. I thanked the mountains for their reprieve, finding myself as just one among countless people who continue to find relief in this special region.