A Conversation With Diane McPhail

07 Feb 2022

An abolitionist’s great-great-granddaughter and her mission to do more good in the world

By Marianne Leek

Birthplace: Jackson, MS

Family: Husband, Ray McPhail; Children, Brad and Melissa; Grandchildren: Logan, Elliot and Amelia

Education: MFA, MA, D.Min.

Hobby: Gardening

John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, once advised people to “Do all the good you can, by all the means you can, in all the ways you can, in all the places you can, at all the times you can, to all the people you can, as long as ever you can.” A poet, writer, artist, teacher, philanthropist, therapist and minister, Diane McPhail has been aptly described as a Renaissance woman. But perhaps what is more important about her is the way in which she lives her daily life, deeply and fully committed to enriching the lives of those around her by empowering others to tap into their creativity, heal from trauma, pursue education, broaden their skills and unconditionally help and love others. Her own creativity, spirituality and humanity permeate every aspect of her life, particularly her relationships and the way she engages with the world around her. And these days that is a rare and beautiful thing.

McPhail is a tireless volunteer and leader within the communities of Highlands and Cashiers, as well as the broader western North Carolina area. I asked her about the nonprofits that are near and dear to her heart. She responded that in addition to the Community Foundation of WNC, local food pantry, vaccination clinics, the International Friendship Center, PAC, and Rotary, “We (she and her husband Ray) are particularly involved with Pisgah Legal Services, the free health and dental clinics, REACH, and The Literacy & Learning Center. Accessible health and dental care are foremost always. If people can't have that, almost nothing else matters. It is the absolute foundation.” While she has served on the advisory board to the WCU Honors College and the board of the Counseling Center for a number of years, McPhail considers herself “more of a hands-on volunteer rather than a meeting attendee.” She explained, “After a presentation at Rotary some years ago by Habitat for Humanity, I asked what they needed most. The answer, as you might guess: money. ‘I know how we can raise a good bit,’ I said. ‘Building birdhouses.’ I think a lot of those guys around me thought I was a bit crazy. But they joined me for more than six months, creating some of the most fantastic birdhouses imaginable. At our fundraiser, we sold 175 houses, some for over $800, and raised over $20,000 to build a house—not for birds!”

As human beings, we have a shared responsibility to give back to our communities and help others. I asked McPhail about the importance of investing in others and how this personal investment has the potential to positively impact communities. She responded that as we transition through difficult times, “There is a great deal that we can do in concert. Just that word gives us a great metaphor. Imagine any one instrument or any voice alone without all the other instruments of the symphony, the other voices of the choir. Think of the harmonies created when people bring their own particular notes to the whole. So much seems broken. I think of the ancient Japanese art of kintsugi, taking the broken and creating beauty. In this process, the broken pieces are glued into place, not to hide the broken places, but to make them more visible, to edge them with gold. The resulting piece is considered more beautiful, more valuable than the original.”

She continued, “I have been saving broken china and ceramics now for years. One of the things I do as a minister is lead an annual retreat for a great group of guys who, spread all around now, originated at Trinity Episcopal in New Orleans. This year would have been our tenth. They are creating an outdoor chapel in my woods and add something to it each year. The year they decided to create an altar, I brought out all the broken ceramic, laid it on canvas with a hammer and pliers, and told them to ‘have at it.’ Initially, they were reticent to break the already broken, but with a little encouragement, they created a magnificent mosaic, each creating their own section, then working them into relationship as a whole. This is community at work. Those birdhouses were community at work. The vaccine clinics are community at work. Our voices in concert, rather than anger and divisiveness, are community at work. Engagement in divisiveness can never win. It can only lose, for everyone. We must find our gold dust, mix it into whatever glue binds us to one another, to create our kintsugi, our community bound together, our brokenness bound again as a unity more precious than winning our point.”

McPhail will proudly tell you that she was and still is an educator. She began her career teaching freshman composition at a community college and later taught English and French at Decatur High School in Atlanta. Since then, she has taught art at the Atlanta College of Art, The Bascom and privately in her studio. As an art therapist, McPhail has helped countless people heal, but she herself has been richly transformed by the experience as well. McPhail explained, “I know from many years of experience working in outpatient mental health and in private practice just how cathartic the creative process can be, both for individuals and for groups. The ten years I worked for Northside Hospital’s outpatient program are the richest and most rewarding years of my working life. They are also the deepest ministry of my life.

Though I did not get to make the trip, I was deeply involved in designing a therapeutic program in art that could be taught to teachers for use with the war-traumatized children of Sarajevo. In completing my doctorate, I designed a year-long series of four retreats that formed one continuous journey to deepening spirituality, regardless of one’s doctrinal religion. Participants signed up for the year to attend all four. For these retreats, there was a creative component to the process every day. Sometimes there might be writing, sometimes artwork, sometimes ceramic work, always music, movement, dance and safety to discuss the experience. It is out of those ten years of retreats that the annual men’s retreat was born, based on creative experience, both individual and communal at every gathering. It is always out of the creative component that growth, change and healing come.”

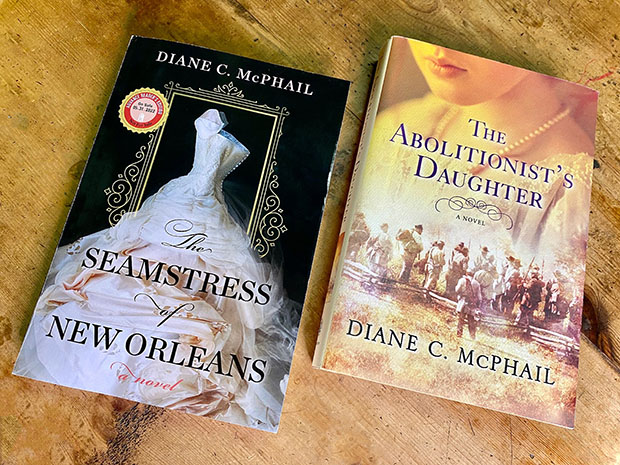

Adding to her long list of accomplishments, McPhail was inspired to write her first novel, “The Abolitionist’s Daughter,” which was published in 2019, when she learned about her family’s history during the Civil War. This history, along with her great-great-grandfather’s role as a Southern abolitionist judge, became the foundation of how she lives her life. Reflecting on over 12 years of research that went into penning her first novel, I asked her what characteristics of her great-great-grandfather can be found in her. “I came to know my great-great-grandfather as a Southern anti-slavery abolitionist judge, unable to free his slaves because manumission had been made a serious crime around 1850. Realizing the creative choices he made in order to do whatever good was possible gave me hope and support for those things I try to do that wind up seeming small, yet are so important to the people involved. He set up a secret illegal school to prepare the slaves for the freedom he believed had to come soon. He acquired slaves put up for sale, conspiring to keep families intact and together. Marriage for slaves had no legal validity, yet as a judge, he married couples, recorded their families with careful records, something that was almost unheard of at the time. My great-great-grandfather has become, for me, an ultimate example of doing what good you can, where you can, even if it fails to change a system beyond your scope. Everything you do makes a difference, even approaching two hundred years later, a difference you may never know.”

On May 31, 2022, McPhail’s second historical novel, “The Seamstress of New Orleans,” will make its literary debut. Pre-release reviews from booksellers and librarians have called it “mesmerizing, fascinating, impeccably researched and impossible to put down.” McPhail explained the premise of her latest work, “Two young women, one recently widowed in New Orleans, the other a fine seamstress in Chicago, pregnant and abandoned, each face immense needs. When fate conspires to bring them together, they discover not only increased independence but a bond of unexpected friendship and ‘found family.’ Yet hovering around them is suspicion of murder and the sinister threat of the Black Hand, New Orleans' organized crime. As the Mardi Gras festivities reach their fruition, a secret emerges that will cement the bond between these two even as it threatens to break apart the lives they have invested everything in building.” “The Seamstress of New Orleans” is currently available for pre-order wherever books are sold.

I asked McPhail about what inspires her creativity, both as an artist and as a writer, her answer is equally profound and beautiful; “Madeleine L’Engle, author of “A Wrinkle in Time,” was my first writing teacher. But long before I began to write, I discovered another book of hers that changed my life— “Walking on Water: Reflections on Art and Faith.” It has been the cornerstone of all my creativity since. Her premise, in a nutshell, is this: The work knows more than you do. It comes to you from somewhere else and, like an annunciation, asks if you will give it birth. If you say yes, your job then is to follow the work where it knows it needs to go. When I simply trust that concept, and I do, and open myself to whatever the work may be, writing, painting, volunteering, without trying to take control of it, things come that astound me, like ongoing miracles.”

When asked if she had any advice for others, specifically those in her community of Highlands, McPhail concluded with the following words, reminding us that we’re all connected: “Trust life. Try not to judge—we usually know far too little of the other’s story to understand. Be kind. Treat others with respect regardless. Look at the world every minute as if you have never seen it before. Pick up a pen or a pencil or a brush. You and every child on the globe started drawing long before you could write or make sentences. So don’t tell me you can’t. Know that you are loved by, in, and through a Divine Mystery that is trustworthy and present, everywhere and in everything.”

She added a final thought, “If I could encourage my community to do one thing? Get to know each other, whether you agree or not. Find someone and do something together for someone else. Maybe all you have to do is smile in passing and say,’hello.’”