The Power of Water in Western North Carolina

03 Oct 2022

Duke Energy’s history of hydroelectric energy in the region

PART ONE

Story by Ben Williamson, Duke Energy

Photography by Chelsea Cronkrite

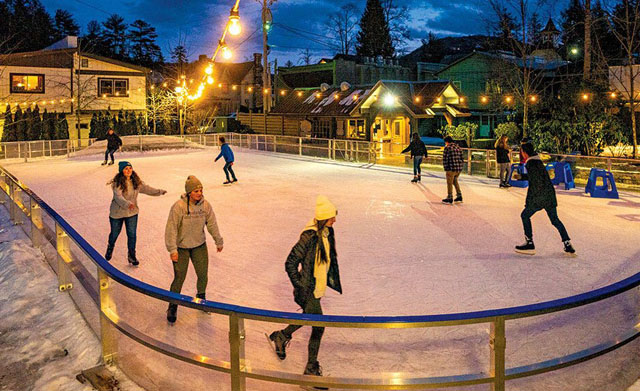

In the mountains of western North Carolina, rolling out of peaks and through the valleys, a vital resource exists – water. That resource, quietly and sometimes not as quiet, is the heartbeat of the region. It’s not an exaggeration to say that without the lakes, rivers and streams, western North Carolina would look very different. The water serves as the backyard to generations of families, some of whom understand the importance and some who may not. For some, their survival depends on the water, and for others, the water provides a simple weekend getaway, a day away from the hustle and bustle of everyday life.

Over a century ago, innovators realized the rare combination of mountains and water that exists among the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina and began using it to transform the region.

Just like the rivers that serve the area, the relationship between Duke Energy and this valuable resource has taken twists and turns. That relationship includes the rapids of the Nantahala River, the quiet mornings on Bear Creek Lake, the weekend trout fishing trip to the Tuckasegee River, the cool dips in Lake Glenville during a hot summer’s day. Among the fields and small mountain roads exists a complex system helping to power the region.

Duke Energy began its operations in the Carolinas as a hydroelectric company. Harnessing the waterpower of the Catawba River, the company’s first power plant provided electricity to the area’s emerging textile industry and, later, the region’s growing appetite for the convenience that electricity could provide. Today, Duke Energy is the second-largest investor-owned hydroelectric operator in the U.S.

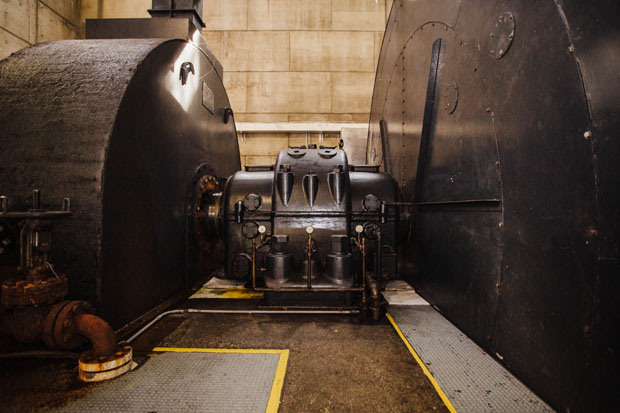

Conventional hydroelectric plants harness the energy produced by flowing water, using simple mechanics to convert the energy into electricity. Water falling from an elevated reservoir drives a turbine to generate electricity that consumers use every day to turn on the lights or charge a cellphone. A hydroelectric project consists of an upper reservoir or lake contained by a dam and flood management features like spillway gates, a penstock that water runs through to the powerhouse, a turbine and generator, which create the energy, and the tailrace, where the water returns to the lower river or lake.

“It is the original green energy. You are using a natural resource to power the lives of communities and you are doing it with very little impact on the environment,” said Allen Nicholson, lead engineering technologist who supports the 11 Duke Energy hydroelectric plants throughout the Blue Ridge Mountains. Nicholson has been with the company for more than 40 years and grew up in the area.

“I was at the right place at the right time. Through my career, I have been given many opportunities. Opportunities that challenged me. Above all, I’ve enjoyed working where I am from. This is my home,” Nicholson said.

Hydropower provides many benefits. Because it uses water as the fuel source, hydroelectricity is relatively inexpensive and environmentally friendly to produce. Additionally, quick startup times make hydroelectric plants ideally suited to both provide peaking (as-needed) power and to adjust generation levels to follow the ever-changing electric demand, thus stabilizing the electric transmission grid.

As Duke Energy continues to increase the amount of solar energy produced, these quick-starting hydro assets are vital. If a cloud covers the sun or a storm blankets the sky and temporarily prevents solar energy generation, Duke Energy can utilize its hydro stations to quickly fill that gap.

In western North Carolina, whether you are a generational family or new to the area, Duke Energy plays a role in your life. From the power you use, the jobs your friends or neighbors may have, the weekends spent rafting down the Nantahala or fishing on the “Tuck,” to hours spent boating on the lakes that Duke Energy manages. The relationship, whether recognized or not, continues to shape the region and the lives of those who call it home.

Of the 28 hydroelectric stations that Duke Energy owns and operates, 11 sit within about a two-hour drive of Cashiers, NC. Steeped with history that defines the region, the plants continue to use this valuable resource to power the lives of so many.

Seven of Duke Energy’s hydros operate and exist within four different federally regulated licenses throughout Western North Carolina. Those licenses are regulated and enforced by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). FERC is the United States federal agency that regulates the transmission and wholesale sale of electricity and natural gas in interstate commerce and regulates the transportation of oil by pipeline in interstate commerce.

The West Fork license includes Thorpe Hydro Station and Tuckasegee Hydro Station, both consisting of a dam and a powerhouse below Lake Glenville. The East Fork license includes Tennessee Creek, Bear Creek and Cedar Cliff hydro stations. Duke Energy also operates under separate licenses for the Queens Creek and Nantahala hydro stations, which are located on the Nantahala River below Nantahala Lake.

The licenses for those seven hydroelectric stations run for 30 years (expiring from 2032 to 2042), but the stations have been in operation much longer. To understand the history of the region and the changes that occurred, you must go back to well before World War II.

In the early 1900s, Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) acquired land in western North Carolina to produce hydropower to power its smelting plant in Alcoa, Tenn. Alcoa formed a subsidiary in 1929 called Nantahala Power & Light Company (NP&L) to serve as a public utility for the Great Smoky Mountains area of North Carolina. NP&L opened its first operation that year in Robbinsville, bringing electricity to the North Carolina mountains and powering 29 customers. NP&L continued to purchase existing dams and power plants as well as build new assets in the area over the next several decades. The war greatly accelerated Alcoa's plans.

At the beginning of the 1940s, the United States, engaged in a world war with Germany, needed additional aircraft bombers, and it needed them quickly. Unfortunately, you can’t make those types of bombers out of just anything — they required lightweight aluminum and a lot of it.

Alcoa, owner of NP&L, just so happened to be the largest aluminum producer in the country and, under the direction of President Franklin Roosevelt, looked for a way to produce the resource fast to support the troops.

Alcoa turned to the waters of western North Carolina for help, quickly constructing the Nantahala and Thorpe hydro powerhouses and damming and flooding Lake Glenville and Nantahala Lake to produce the large amounts of electricity needed to power aluminum sheet metal production for Allied aircraft. At the time, both dams were higher than any similar dam that had ever been constructed in the eastern half of the United States.

Both the Thorpe and Nantahala hydro developments are unique in that their penstocks – the tunnels that carry water from the upper reservoir to the powerhouse – are several miles long. Tunneled through mountain rock, the penstock for the Nantahala powerhouse is over 5 miles long, and the penstock for Thorpe is nearly 3 miles long.

“You sit back and marvel at the engineering challenge these plants were. They blasted and built these tunnels in a mountain, and they did it in less than two years. Today, something similar may take many years,” said Preston Pierce, the general manager for Duke Energy’s 11 hydroelectric plants that sit in the western footprint. With the company for more than 25 years, Pierce overseas the seven legacy NP&L hydro plants.

According to a news article from that period, “More Power for Bomber Productions,” the new power plants could produce, “enough aluminum to build 1,230 ‘Flying Fortress’ bombers.” In the 1940s, the Thorpe and Nantahala hydro developments enabled Alcoa to produce enough aluminum to pump out two bombers a day.

“I am a firm believer that these hydro plants helped us win the war and it is an engineering feat that they were able to get these dams and hydro stations built so quickly,” said Nicholson.

By the mid-1940s, the war was over, and the infrastructure was producing much more energy than was needed for military efforts. Seeing an opportunity, NP&L managed the power system and built hundreds of miles of transmission lines through the region.

“My father was a lineman who was hired by NP&L in 1941,” said Lisa Leatherman, a community relations manager for Duke Energy. “He would share stories with me about building power lines to people’s homes in the region where the customers’ first use of electricity was just a lightbulb. They didn’t have refrigerators; they didn’t have the electric iron. They were just happy to replace the oil lamp.”

Leatherman’s father worked for NP&L for 45 years, and she started her career with NP&L. Leatherman has now been with Duke Energy for more than 35 years.

“When I was kid, if a storm caused a lot of outages, people would call our home. I remember thinking it was pretty cool to have a notepad to write down the names and phone numbers of people who my dad would then go help. He would get the lights back on,” said Leatherman.

NP&L is credited with being a catalyst of economic development and social change in western North Carolina as electricity was delivered to areas that had never had it. That growth continued for well over a decade. By the 1950s, NP&L had increased its customer base to 8,373, which was 95% of area residents. And even after WWII, aluminum continued to be indispensable, becoming a main product for siding, doors and packaging, as well as instrumental for aircraft needs for the Cold War and Korean conflict. Alcoa, owning and operating its own power sources, kept these material prices low.

“The areas around the hydro stations flourished. The hydro stations provided jobs, power and the economic benefit to keep the region afloat,” said Pierce.

For years, NP&L was integrated into the community. The main office was in Franklin, N.C.

“We had about 200 employees and it was kind of a family. At one point, I think I probably knew everyone,” said Kevin Holland, who was with NP&L for nearly a decade before the Duke Energy acquisition. A Franklin native, Holland now serves as a Duke Energy Lake Services representative overseeing the lakes that make up the system in western North Carolina. “Growing up, I understood the lakes were around but didn’t understand who owned them or why they were there.”

During the 1940s and 1950s, NP&L constructed additional hydroelectric projects. In the Nantahala region, Queens Creek plant was built in addition to two small dams: Whiteoak Creek and Dicks Creek, which provide additional water for minimum flows and to fuel the Nantahala hydro plant.

Shortly afterward, NP&L completed the construction of the Tuckasegee Hydro Station that sits just downstream of Thorpe Hydro Station. To provide additional power, the company also completed hydro stations at Bear Creek, Cedar Cliff and Tennessee Creek.

“The engineers who created these things were brilliant. They mapped everything; they sketched everything on paper. It was amazing,” said Nicholson.

The legacy NP&L plants are eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, a designation that brings protective processes to ensure their historical integrity is preserved.

“History lives in these plants. I have seen the buildings change some and I will grab labels from equipment that is being retired or replaced and put those on the shelf. History is a big part of this, and we can’t lose that,” said Phil Postell, who oversees operations at Thorpe Hydro Station for Duke Energy. Over 25 years, Postell has held multiple positions from operations to technology and currently is the Nantahala area station manager.

As the region grew and the population increased, NP&L continued to serve customers through its own energy generation while also purchasing power from what was then known as Duke Power. In 1988, Duke Power acquired NP&L, in part to connect Duke Power’s transmission grid to the much larger Tennessee Valley Authority company. This acquisition better connected the Southeast as the population continued to grow.

Jeff Lineberger is Duke Energy’s director of water strategy & hydro licensing, and he was the lead negotiator for the company in the stakeholder-driven process used to shape the new FERC licenses. In over 30 years with the company, he has participated in relicensing of all but one of the company's hydropower stations.

“NP&L was a small system, but it was an important system,” said Lineberger.

These seven legacy hydroelectric stations that help provide energy to the region can generate nearly 90 megawatts. One megawatt can power 800 homes, on average.

During the first decade of the 21st century, Duke Power faced the challenge of relicensing all the hydropower assets that had belonged to NP&L – no small task considering the two companies had just integrated their management structures in 2000. In a way, Duke Power was a stranger in the region – trust didn’t exist at first.

Leatherman described the transition as “challenging at first.” Most NP&L customers were used to visiting one of the local offices to pay their power bill. As time passed, those offices closed and Duke Power managed operations much differently than what the region was accustomed to.

“It was important for Duke Power employees to take time to learn how NP&L had operated and managed the hydro projects and how neighboring communities' interests were interrelated,” said Lineberger. “We weren’t going to come in there and just take over. We also had some exceptional teachers and role models on the team, including the late John Wishon, Fred Alexander and Gary Morgan of NP&L and Elizabeth ‘Bunny’ Johns, who was a true pioneer for the whitewater paddling industry in the area."

What followed were years of studying hydro project impacts, testing solutions, negotiating competing interests, finding common ground and “‘long drives with a lot of thinking” as each hydroelectric project was relicensed.

“I think people slowly started to see that Duke Power was here to help. They started to see the benefits that the company provided,” explained Holland.

To understand the relicensing process would take longer than this article allows, but Duke Energy's version of it is a multiyear process where stakeholder interests are considered with the goal of reaching an agreement that everyone supports.

“During these relicensing efforts, we learned how to actively listen to people without getting defensive and learned how to find elegant solutions to complex problems in many cases. Relationships were strengthened. Although we didn't reach agreement with 100% of those involved, we learned how to disagree without being disagreeable,” said Lineberger.

All the projects were eventually relicensed except one – Dillsboro Dam. You can’t discuss Duke Energy’s history in this region without discussing Dillsboro Dam. Located in the town of Dillsboro along the Tuckasegee River, the dam and powerhouse comprised the smallest FERC-licensed project in Duke Energy’s history.

Constructed in 1913, the original purpose was to supply power to the Blue Ridge Locust Pin Factory; it was acquired by NP&L in 1957.

During the relicensing process, many stakeholders expressed interest in removing the dam to improve river habitat for native aquatic species and allow an unhindered fish passage upstream. In their minds, the dam had a negative impact on the environment, as well as providing an impediment to recreational navigation.

After intense negotiations, in 2003 Duke Energy and interested stakeholders signed comprehensive relicensing agreements addressing the issues at most of the company's hydro projects in the region, and that included removal of Dillsboro Dam.

The removal didn’t come without significant pushback. Many felt the iconic structure was important to the area's history and taking it down would be an insult to previous generations.

“The dam with its constant waterfall was also one of the most photographed sites in the region at that time. There were many people who didn’t want that attraction to be removed, and we understood that,” said Lineberger. “Those were some important and difficult conversations that got very emotional for some.”

In the end, the dam was removed and by 2010, the river once again flowed freely through the town of Dillsboro. In fact, the dam’s removal exposed a beautiful natural rock cascade. It is still a destination spot for many, and tubers, kayakers and other boaters now enjoy the river as it once was before the dam was constructed.

As was the case with Dillsboro and Duke Energy's other hydroelectric projects, the primary function was electric generation. However, as Duke Energy worked to relicense each of these projects, the objectives broadened. The public and its interests were an integral part of the process to shape the new license.

“These hydroelectric plants still provide clean, renewable electricity, but they also provide much more. Hydro is a place where we really get at supporting our communities. We live our mission. It is not an afterthought,” said Lineberger.