The Pioneer Preservationist

05 Feb 2024

Dr. Carl Schenck, the Vanderbilts and the Cradle of Forestry

Story and photos by F.B. ROBINSON

Just outside Brevard lies the entrance to Pisgah National Forest. Highway 276 takes you along the scenic Davidson River, past the often-photographed Looking Glass Falls, and just beyond, the regionally famous Sliding Rock. Continue up the mountain, and four miles below the Blue Ridge Parkway, the road bisects an important slice of American history. It is a history that continues to impact us daily. Without it, the magnificent forest surrounding you today would likely not exist.

The Cradle of Forestry’s origin traces back to 1888. It was the year George Washington Vanderbilt, a member of the wealthiest family in the United States, visited Asheville, North Carolina. He came seeking malaria treatment for his ailing mother and soon fell in love with the area. Thinking it would be an excellent place for a home, he began purchasing parcels of land. To avoid inflated land prices, the tracts were registered in the names of his lawyer and land agent.

After procuring approximately 2,000 acres, Vanderbilt hired Richard Morris Hunt, the foremost architect of the time, to design the mansion that would come to be known as The Biltmore House. He also hired Frederick Laws Olmstead, a nationally prominent landscape architect whose projects included New York City’s Central Park. Before breaking ground for the 255-room home, Olmstead erected several viewing towers on the property to better orient the house, allowing Vanderbilt the opportunity to consider the spectacular views he would be afforded. Vanderbilt was so impressed, in particular with Mt. Pisgah, which stood proud on the crest of the Blue Ridge, that he acquired more and more parcels.

Olmstead soon realized the need for management of Vanderbilt’s vast land holdings as much of the newly purchased acreage had suffered from fire damage, aggressive farming and poor logging practices. Olmstead recommended Vanderbilt hire a forester, 27-year-old Gifford Pinchot, to oversee the land. Pinchot was a graduate of Yale and had studied forestry in France. At that time, there were no schools of forestry in the United States.

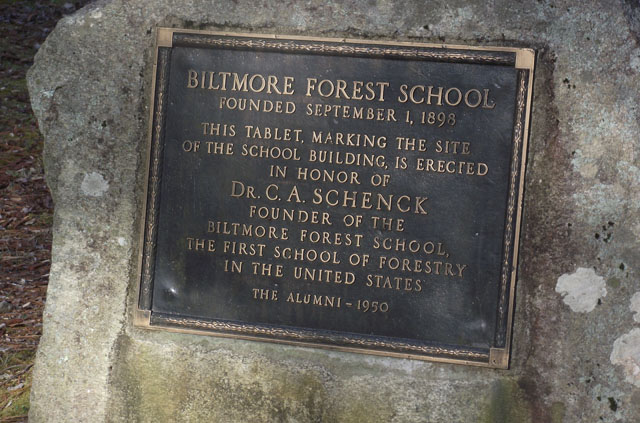

Vanderbilt hired Pinchot in 1892. Under Pinchot’s tenure, Vanderbilt’s holdings increased to an astonishing 100,000 acres. Pinchot is credited with the first scientific forestry management plan in the United States. However, Pinchot held forestry aspirations on the national level as well, and he left Vanderbilt’s employment after only three years. Before doing so, he recommended Dr. Carl A. Schenck as his replacement. Schenck had studied forestry in his native Germany and arrived at the estate without much knowledge of the wide variety of hardwood and conifer species found in western North Carolina, nor about the unique culture of its people. Before Pinchot’s departure, he and Schenck rode to the base of Mt. Pisgah where they spent time discussing the future of the vast tract of land.

It didn’t take long for Schenck to understand he was overmatched by the size of the project and needed help. Without a source to provide skilled assistants, he came to the realization that he would have to manufacture his own.

On September 1, 1898, Schenck opened the Biltmore Forest School, the first school of its kind in the United States. The tuition was $200 per year, plus an additional $330 for room and board, the combined sum of which is approximately $18,000 in today’s dollars. Each student was required to provide their own horse. Winter classes were held in Biltmore Village, and the field work was conducted on the estate. The rest of the year, the campus moved to its present location, a valley referred to as The Pink Beds. The students lived a Spartan lifestyle, often staying with settlers who had refused to leave even after Vanderbilt’s purchase. Some lived in small groups in abandoned, often-derelict cabins. These structures were given colorful names including, Gnat Hollow, Rest for the Wicked, Little Hell Hole, and not to be outdone, Big Hell Hole.

Although Schenck followed several principles of his predecessor Pinchot, their philosophies did not align in every way. Believing that proper forest management should result in preservation and sustainability, as well as profit, Schenck soon added his own curriculum. It was important to Schenck that Vanderbilt receive a return on his immense investment, but he understood there was more at stake. Classwork still took place in the mornings, followed by a brief break for lunch, but then students would spend the afternoons riding into the forest for hands-on training with Dr. Schenck. Sometimes the rides would be as long as 20 miles. It was often hard work. Trails had to be established to access areas of the forest. Roads, and occasionally bridges, had to be established for harvested timber to be brought to market.

After a year of intense instruction, requiring mastery of 27 subjects, each student was required to complete a six-month internship. Often, this internship would take place under Schenck’s tutelage, as he was regularly in need of management assistance overseeing Vanderbilt’s land holdings, which had now grown to a whopping 125,000 acres. After successful completion of the internship, students were awarded a Bachelor of Forestry Degree.

By 1909, due mainly to bad investments, the 1907 crash, and maintaining an ultra-extravagant lifestyle, George Vanderbilt had sustained significant financial setbacks. He wanted to sell his entire parcel of forest, but Schenck resisted the idea. Furious, Vanderbilt fired Schenck, thus bringing an end to the Biltmore Forest School. Believing deeply in his mission of preservation, Schenck began teaching in “traveling schools” until established universities, including Cornell and Yale, started forestry schools of their own. It should be noted that by 1913, Schenck had graduated over 400 students, and seventy percent of all certified foresters in the United States were the product of the Biltmore Forest School.

The original Cradle of Forestry opened in 1965 but was lost to fire in 1985. Today’s Cradle offers a modern museum with movies, and a simulated helicopter ride for kids and adults. There are several paved trail loops, one which leads you past the steam engine used to haul lumber and some of the original structures that made up the Biltmore Forest School. There is also an exact replica of the one-room school where Dr. Schenck taught the first generation of American foresters. Plan on spending a few hours to give yourself enough time to appreciate the entire experience. The Cradle of Forestry is open 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Wednesday through Monday, spring through fall. For more information, go to https://gofindoutdoors.org/sites/cradle-of-forestry/ or give them a call at 828-877-3130.