Protecting the Plateau

02 Aug 2022

Highlands-Cashiers Land Trust saves special places

Article and photos by Brendon Voelker

A towering grandstand along the North Carolina and South Carolina border, Whiteside Mountain rises over 1,500-feet to the Highlands-Cashiers Plateau with views reaching far into Georgia on a clear day. Known locally as the Blue Wall, the area was devastated by logging in the late-19th and early 20th-centuries. Cearcutting, a practice in which most or all trees in an area are uniformly cut down, was a common practice throughout much of the timeline. Prior to that, small-scale mining operations and indigenous trade routes trampled through the region.

Since 1909, a local land trust has been paving the way for conservation and preservation of native plants, wildlife and open spaces across the plateau. The largest landowner in the Highlands area, the Highlands-Cashiers Land Trust (HCLT) is the oldest land trust in North Carolina and among the first 20 in the United States.

The group spearheaded this movement with trail-building and tree-planting improvement projects. In 1909, the HIA collected $500 and bought 56 acres on Satulah Mountain that was slated to become a hilltop hotel.

“The Highlands community thought it better to look at a mountain rather than a hotel,” according to the group.

According to Gary Wein, executive director of the HCLT, the 501(c)3 non-profit organization holds and maintains roughly 300 acres associated with the town of Highlands with a goal "to protect valuable natural resources for all generations." Land was accumulated through direct purchases by the organization and land donated for preservation by landowners and families.

The headwaters to six distinct watersheds are found on HCLT properties. The protection of clean drinking water for the greater Southeast is a top priority, Wein said.

Conservation easements and land trusts are often misunderstood. In short, a private landowner can work with a land trust to place a portion of their land into a conservation easement. That easement is then perpetually protected from future development, a status that can only be reversed in court.

In exchange, the landowner receives a reasonable tax break and maintains ownership of the land, but gives up all rights to develop or modify it. That doesn’t expressly mean it can’t be developed for public access, but it allows wildlife, wildflowers and other natural resources to be protected from future human impact. In many cases, public access could go against the goal of conservation in the first place.

Wein was kind enough to take a few hours of his day to show off a prized HCLT property on Satulah Mountain just minutes from the group’s headquarters.

As we step out of the car, my eyes lock on a tree casting a shadow over the hood of the car. It’s a Chinquapin, related to the American Chestnut, and partially resilient to an invasive blight that killed off nearly every American Chestnut prior to the turn of the 20th century. By some estimates, American Chestnuts accounted for nearly 20-30% of our local forests prior to the accidental introduction of the blight.

Other rare and important plants Wein pointed out include granite dome goldenrod, Hartweg’s locust, dwarf juniper, krigia, oat grass and sphagnum moss as we look east towards Whiteside Mountain. The distinct profiles of Rock Mountain, Chimney Top and Toxaway Mountain define the foreground, while the faded peaks of the Great Balsam Mountains and the Blue Ridge Parkway can be seen amongst the blue haze in the distance.

The Blue Ridge Mountains earn their name from a chemical reaction from the plants combined with photosynthesis, a cumulative effort that gives this massif of the Appalachian Mountains a blue haze.

The largest known hemlock in the east coast, nicknamed the “Cheoah,” can also be found on HCLT lands, though its location is a closely guarded secret. In 1930, an invasive pest began attacking eastern hemlock trees in the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia and has since spread to most of the East Coast. Gary states that protecting flora and fauna is just as important as protecting the environment which they thrive in, which is why there is a large focus to protect exposed rock outcroppings and granite cliffs.

HCLT is composed of five staff members, plus an AmeriCorp member. Public-access properties include Ravenel Park, McKinney Meadows, Brushy Ridge and Dixon Woods Park. Rhodes Big View, a roadside pull-out where you can view the “Shadow of the Bear,” is also protected by the HCLT. Other notable properties include the top of Laurel Knob, Pinky Falls, and Little Scaly Mountain.

Each property preserved by the HCLT hosts unique or unusual flora and fauna and you can learn all about them on a scheduled EcoTour led by Wein himself. He describes the tours as a way to acquaint the public with their properties, many of which are only open to the public for special occasions.

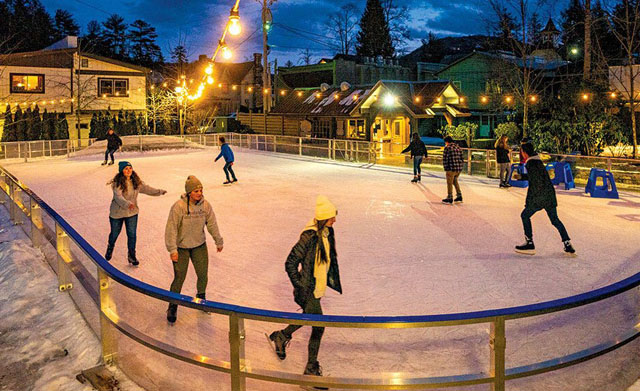

Events like pop-up hikes and weekly talks at the Village Green in Cashiers are other ways to get involved and support HCLT’s work.

Learn more about the HCLT, the conservation process and consider donating to the organization or placing a portion of your land into a conservation easement to protect it from future development at www.hicashlt.org.